Adults at Crumpsall Workhouse, Manchester, c.1897. Source: Manchester Archives. [We have not found any photos of Sheffield workhouse inmates.]

The Boards of Guardians of the two workhouses in Sheffield paid for the funerals of people whose family could not afford to pay. These were often people who had died in the workhouse but this could also be a form of ‘outdoor relief’ for families living in their own homes. Where a workhouse inmate’s family could afford to pay for the burial then the Guardians would expect them to do so, and the family would want to do this to avoid the stigma of a pauper funeral.

The Ecclesall Union workhouse in Nether Edge was close to the Sheffield General Cemetery, and all their pauper funerals took place in the Cemetery. About 10 per cent of burials in the Cemetery have a last residence recorded as a workhouse, reflecting the fact that people often entered the workhouse when sick or aged. The exact number of pauper burials in the Cemetery isn’t known but it is likely a good proportion of those who died in the workhouse would have had pauper funerals.

The Ecclesall Union workhouse had its own hearse which would have been driven by a workhouse inmate and would have been instantly recognisable to passers-by as a pauper funeral. People’s fear of entering the workhouse was increased by fear of being buried as a pauper and the even greater fear that their body might be sent for dissection. The Anatomy Act of 1832 permitted workhouses to sell paupers’ bodies to medical schools for dissection, providing the pauper had no living relatives or friends to claim the body.

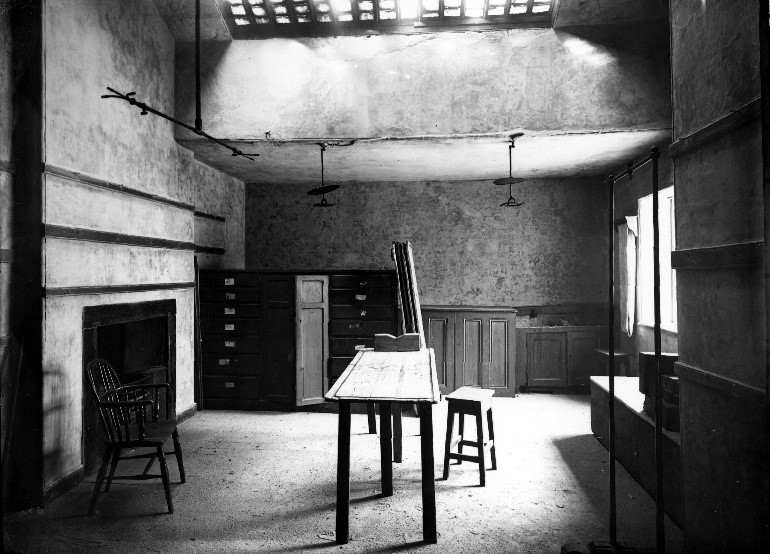

Dissecting Room, Sheffield Medical School. Source: Picture Sheffield.

The General Cemetery has 56 burials that all have a last residence of ‘Sheffield Union [Medical School]’ in the period 1869 to 1880. Each of these burials has a gap of four to six weeks between date of death and date of burial showing that their bodies had been sold for dissection. As there was no refrigeration then the remains must have been significantly decomposed by the time they were buried. It has been difficult to learn very much these people as we have only a name and age. One of these was William Stringer who died at the age of 70 on 27 March 1876, and was buried on the 5 May. He had two criminal offences – the first was for ‘lodging out’ (ie rough sleeping) for which he received two months hard labour; the second for ‘absconding with Union clothing’ in 1864 when he was described in the court records as a cutler. There are no census records for him suggesting he may often have been of no fixed abode. William’s remains were buried in public grave K3 126 in the Anglican area of the Cemetery.

In 1882 there was an unfortunate incident which became know as the ‘Sheffield Workhouse Scandal’ when the wrong body was sent to the medical school for dissection. A young woman asked to see the body of her husband who had died in the workhouse and was horrified to see instead the body of an old man. Her husband’s body had already been sent to the Medical School where it had been shaved but fortunately not dissected.

All pauper burials would be in public graves as this was the cheapest form of burial. These were plots which belonged to the owners of the Cemetery rather than to a private individual and were used to bury the bodies of unrelated individuals. These graves were not marked with any kind of headstone, so the occupants were not formally commemorated. Although paupers were buried in public graves the majority of burials in public graves were not paupers, so these are not ‘pauper graves’.

The poor quality of coffins supplied to the workhouses was often discussed at Guardians’ meetings. The need to keep costs down led to contracts being given to the lowest bidder, who then cut costs by providing inferior coffins. In 1867 a letter was sent to the Sheffield Daily Telegraph describing ‘an ill-shapen, thrown together piece of timber that stood the place of a ‘coffin’ without a coffin plate on it, which presented a most repellent aspect’.

In 1873 a Board of Guardians meeting reported in the Sheffield Independent highlighted the extent of the issue:

Mr Bacon … informed them that he had on one occasion seen three pauper interments at the General Cemetery and that in each case the coffin lid was split … the bodies were buried one upon the other, and that the last coffin was within a foot of the surface!’

He finished with:

Respectful consideration of the dead is one of the characteristics of civilised communities, and that consideration should certainly be paid to the poor humanity of pauper. I had hoped the time was gone by when these lines would have any truth in them:

Rattle his bones over the stones

He’s only a pauper who nobody owns

But I am sorry to say that recent events have proved they are still true, and there is almost as much necessity as ever for a strict watch to be kept over officious but negligent bumbledom.

The Sheffield General Cemetery Company confirmed at a subsequent Board meeting that Cemetery policy was to refill public graves after each individual burial.

More fascinating information about workhouses can be found here and in the Sheffield General Cemetery Trust’s publication A Window into the Workhouse.