South East View of Sheffield 1855 by William Ibbitt. Source: Picture Sheffield.

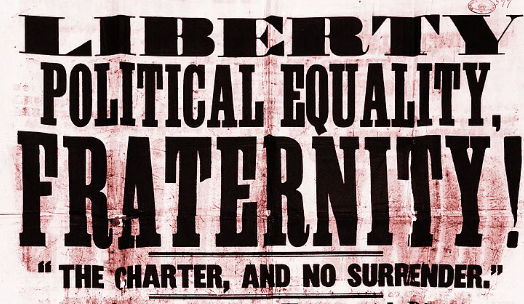

At the turn of the eighteenth century radical and revolutionary ideas were spreading rapidly in Sheffield helped by its special set of circumstances.

The town was administered in an informal way. It was freer in style than many others because it was not tightly controlled by an aristocrat or town corporation. Though surrounded by the estates of the Earl Fitzwilliam, the Duke of Devonshire and the Duke of Norfolk, none of them controlled town affairs. Neither did it have a town corporation but instead there were three historic bodies, the Church Burgesses, the Cutlers’ Company and the Town Trustees, all of whose powers and resources were limited.

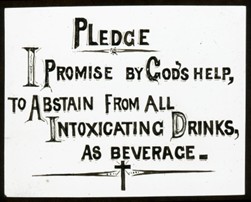

Sheffield had considerable religious diversity and the strong influence of dissenters. This included highly educated and prominent citizens who before 1828 were denied access to public office and votes in elections. Dissenters resented these restrictions and leaned towards radical politics. Sheffield also had a strong temperance movement encouraging people to sign pledges to abstain from alcohol and campaigning for prohibition. Many nonconformists were also temperance campaigners.

At the same time Sheffield’s industrial developments led to growing tensions between the artisans and the master manufacturers. The artisans were mostly semi-independent, literate and numerate although vulnerable to adverse trading conditions, to sharp practices and to the master manufacturers who increasingly dominated their trades.

During this period Sheffield was one of the main centres for trade union organisation and agitation in the UK. In the 1860s this culminated in the Sheffield Outrages where acts of violence took place against employers and those who had not joined the Unions.