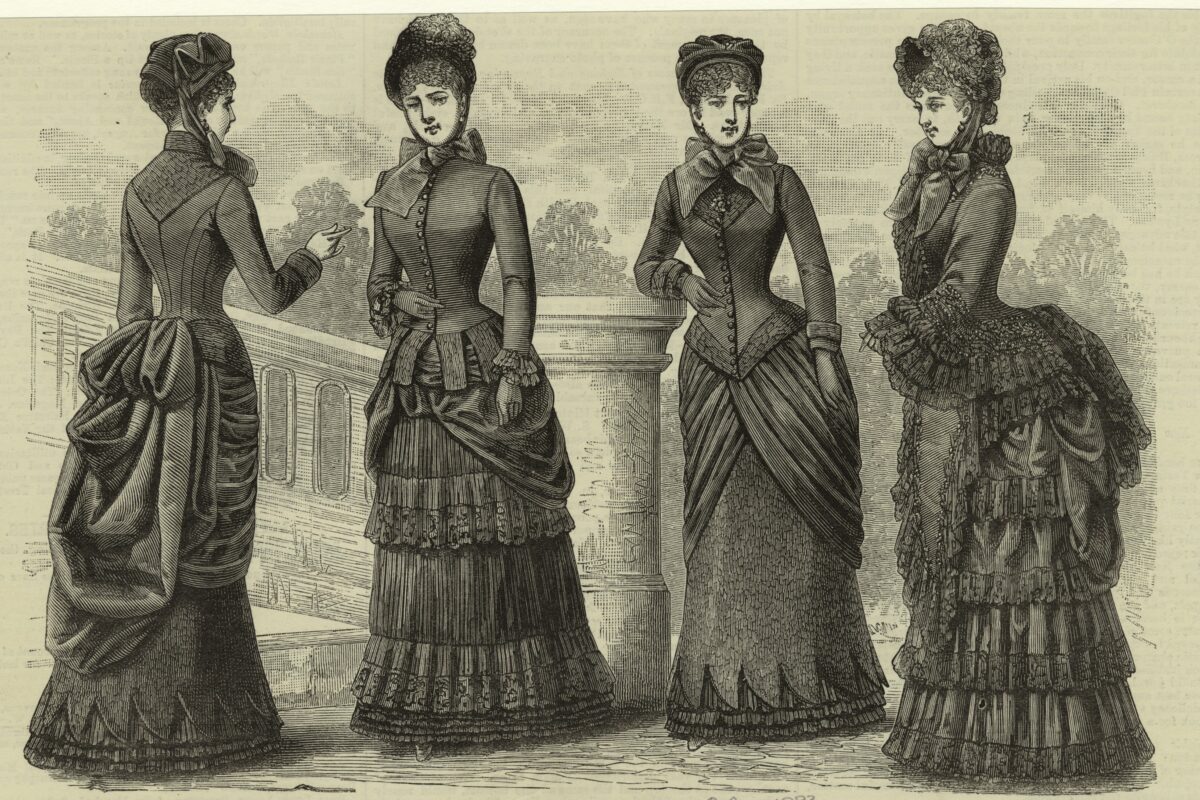

Mourning Costumes from The Queen [published London) 1883. Source: New York Public Library.

This very public response to the death of a loved one had a major impact on the styles of mourning and funerals adopted by the middle and upper classes. Before Queen Victoria dark colours were generally worn for mourning, but there was no formalised system directing who should wear what clothing and when. After Albert’s death the length of the mourning period, the considerations of appropriate clothing to be worn, funeral carriages and processions, the nature of wakes and the refreshments served – in fact every possible aspect of acknowledging a death – was now elaborated and established in a set of informal but well-recognised rules. Observance of these rules could be very costly and was by no means available to every section of society.

However, for those who were able to afford it, and who cared about what their social peers might think, there was strict etiquette to be observed for funerals, as for most aspects of Victorian life. Respectable Victorian society was dominated by men and their rules affected all aspects of women’s lives. A widow could be obliged to wear deep mourning dress for a year and a day and wasn’t allowed to accept invitations for the first year. After that, if her social status and income allowed, she would wear a black dress and mantle (cape) with black crepe trimming on the dress. Her bonnet would be covered with a crepe veil and even her underwear might be threaded with black ribbon. Two years after her husband’s death she might vary her colours with purple, grey or mauve, and it was then harder to distinguish mourning clothes from other correct dresses. But it was the material as much as the colour which revealed mourning dress. Coburgs and henriettas were both forms of woollen cloth frequently used for mourning dress, but it was crepe more than any other fabric which achieved mourning status in spite of the fact that it was uncomfortable to wear, being coarse and scratchy. Mourning jewellery was also popular, particularly Whitby Jet, a form of black fossilised wood only found in Whitby in North Yorkshire and a whole industry was created there with 200 workshops. Later, less expensive ‘black glass’, also called French Jet, took over and the Whitby trade declined.

High mortality rates meant women could wear mourning for much of their lives. Indeed new wives of widowers were expected to wear mourning for their predecessor and therefore to dress only in black or shades of half mourning. And, if the family were wealthy enough, even the staff would wear mourning dress.

Men’s funeral dress was much easier. They simply wore dark suits with black gloves, hatbands and cravats. They were expected to mourn their wife for just three months and during that time could still undertake business and attend social events. This did not mean they grieved any less but was rather a reflection of the yawning gap between the social expectations demanded of women and men.

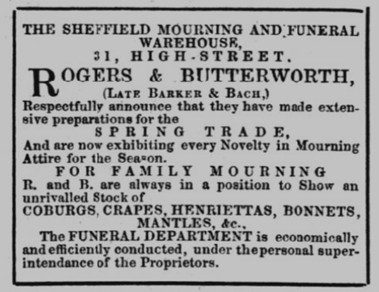

There were many notable emporiums in Sheffield where the discerning shopper could buy their respectable and extensive mourning wares. The strict rules of mourning etiquette allowed businesses to make money by dressing an entire family, including children and servants, in appropriate clothes. Of course not everyone could afford a set of new mourning for each new bereavement, but for those that could the correct mourning wear meant keeping pace with changes in fashions, as in this advertisement placed by Rogers and Butterworth, offering ‘every Novelty in Mourning Attire for the Season’.

Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 7 April 1857. Source: Sheffield Local Studies.